Abstract: The October 2015 emergence of the Islamic State in Somalia has led some observers to wonder if its presence poses a legitimate challenge to the jihadi hegemony exerted by al-Shabaab. However, al-Shabaab far outstrips it in three domains: capacity for violence, ability to govern, and media and propaganda efforts. Though the Islamic State in Somalia remains unlikely to threaten al-Shabaab’s hegemony, scenarios that could at least lead to a greater parity between the groups include greater coordination between ISS and Islamic State central, and the degradation of al-Shabaab by the multinational AMISOM force.

Since 2007, al-Shabaab has ruled the roost as the most powerful jihadi group in Somalia, and indeed, the Horn of Africa. Yet, the longevity of this supremacy came into question in October 2015 when Abdulqadir Mumin,a a former al-Shabaab ideologue who was part of a Puntland-based faction of the group, defected from the avowed al-Qa`ida branch and pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the Islamic State. Over time, an intra-jihadi battle of sorts has arisen. The Islamic State has begun courting and converting al-Shabaab members, and in response, al-Shabaab has been waging an internal counter-messaging campaign, in addition to employing violence against members of the Islamic State as well as its own members sympathetic to the Islamic State cause inside Somalia.

With the presence of both al-Shabaab and the Islamic State in Somalia (ISS) in the country, sundry observers have wondered aloud: could the Islamic State in Somalia challenge al-Shabaab for land, legitimacy, or influence?1 Or has al-Shabaab sufficiently cemented itself in Somalia so as not to seriously face a threat from the relatively new Islamic State-aligned Somalia group? More broadly, what impact might the presence of two groups—one an al-Qa`ida branch and the other an Islamic State affiliate—mean for peace and security in Somalia? This piece traces the four periods in the ISS and al-Shabaab rivalry—starting with the emergence of ISS; the Islamic courting of al-Shabaab members; al-Shabaab’s attacks on its own pro-Islamic State members; and al-Shabaab attacks on Islamic State cells in Somalia.

Chronology of the Dispute

Phase 1: The Emergence of the Islamic State in Somalia

While much has been written on the emergence of al-Shabaab, which formed as a violent arm of the Islamic Courts Union in Somalia in 2006 when Ethiopia invaded the country,2 far less is generally known about the Islamic State in Somalia. The Islamic State in Somalia emerged in mid-2015, with two factions arising in two different parts of the country. The first and most well-known of these is what most commentators today refer to as the Islamic State in Somalia. ISS was founded in October 2015 when Mumin, at one time an al-Shabaab ideologue stationed in Puntland defected from al-Shabaab and pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi and the Islamic State in that same month.b Although the ISS remained generally inactive for the first year or so, its emergence as a real threat came in October 2016 when it briefly invaded and held the Somali port city of Qandala. Since then, it has been increasingly active.

While Mumin’s Puntland-based ISS has been the most visible Islamic State cell in Somalia, in fact, other pro-Islamic State cells in Somalia, based in the southern parts of the country—and apparently without formalized names—emerged even before his outfit, pledging their loyalty to al-Baghdadi and the Islamic State prior to October 2015. However, these did not gain any traction until more well-known al-Shabaab commanders, such as Bashir Abu Numan—a former al-Shabaab commander and veteran of the jihad in Somalia who had fought for one of al-Shabaab’s predecessor groups, al-Ittihad al-Islami—left al-Shabaab in late 2015 and pledged allegiance to the Islamic State. Nevertheless, these southern Islamic State cells remain less well-known, and pose less of a threat, than Mumin’s ISS. And while it appears likely that Mumin acts as the overall leader of Islamic State-loyal forces in Somalia, the connections between his group in Puntland and those in the south are fuzzy.c

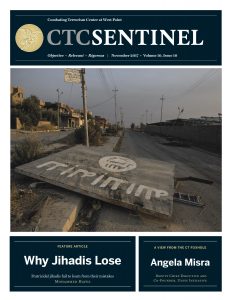

Abdulqadir Mumin is pictured at an ISS training camp named after Bashir Abu Numan somewhere in Puntland, Somalia, in 2016. (Furat)

Phase 2: The Islamic State’s Overtures to al-Shabaab

The genesis of the conflict between al-Shabaab and ISS began not on the battlefield, but online, as the Islamic State began to court al-Shabaab away from al-Qa`ida to join the caliphate. The first instances of the Islamic State’s calls to al-Shabaab were done through informal channels, followed eventually by formal pleas. The first instance identified by the authors came in February 2015 through the Global Front to Support the Islamic State media. An article authored by Hamil al-Bushra implores al-Shabaab to join the caliphate, asking in its conclusion, “when will we hear, oh dear brothers, of Wilayat al-Somal?”3 A resumption in overtures occurred in September 2015 when two more products were released. After a shorter article was released in al-Battar on September 23, 2015,4 the main informal pleas came from three articles in the Islamic State’s unofficial al-Wa’fa Foundation media outlet, released on September 27, 29, and 29, 2015, respectively.5 The first, targeting al-Shabaab, lays out the principles for legitimacy of the Islamic State and the obligations for pledging allegiance to it. The second article argues that after the establishment of the caliphate, all other groups are null, specifically underlining the illegitimacy of al-Qa`ida, al-Shabaab’s adopted parent organization. The third article focuses on the apostasy of al-Qa`ida and puts forward evidence of its purportedly shifting creed. In each of these early cases, the Islamic State’s calls to al-Shabaab were generally respectful and laudatory, referring to al-Shabaab members as “steadfast mountains” and “roaring lions” and the “new generation of the caliphate.”6 Moreover, in early calls, the Islamic State assiduously avoided critiquing al-Shabaab’s leadership, leveling attacks instead at al-Qa`ida.

The Islamic State’s first official outreach to al-Shabaab occurred in a series of five videos released by various wilayat, or provinces, of the Islamic State, through each of their official media wings. On October 1, 2015, three wilayat—Ninawa,7 Homs,8 and Sinai9—released such videos, while Raqqa10 released one on October 2 and Baraka11 on October 4. Each of these videos broadly made the case that al-Shabaab should join the caliphate, simultaneously underlining the illegitimacy of al-Qa`ida.

Al-Shabaab did not take kindly to such overtures. However, the group has still never publicly released an official statement about the situation, mimicking the general approach taken by other al-Qa`ida affiliates courted by the Islamic State at the time. Instead, pushback against the Islamic State came only occasionally from individual al-Shabaab supporters online.12 That said, while al-Shabaab was officially silent on the Islamic State’s invitation to abandon an al-Qa`ida allegiance in the open, a different story was playing out internally.

Phase 3: Al-Shabaab Attacks on its Pro-Islamic State Members

Rather than lash out directly against the Islamic State, al-Shabaab’s ire at the suggestion that it abandon its links with al-Qa`ida was mostly directed toward its own members who showed sympathy to the Islamic State. Indeed, since at least 2012, when members began to publicly criticize the leadership of Ahmed Godane,13 the group has endured internal ideological fissures that have threatened to destabilize it,14 and the question of how to respond to the Islamic State served as another flashpoint capable of dividing the group. As researcher Christopher Anzalone neatly articulates: “Though the Islamic State’s ideology, or aspects of it, are attractive to some members of al-Shabaab, the emergence of such a competitor [in the Islamic State]…provides those disgruntled members [of al-Shabaab] a way to challenge the status quo” of al-Shabaab’s operational culture.15

Thus, as early as September 2015, reports suggest that al-Shabaab was beginning to detect and silence pro-Islamic State sentiments within its ranks. According to one report, in that month, the group issued an internal memo that “stated the group’s policy is to continue allegiance with al-Qaeda and that any attempt to create discord over this position [by suggesting an alliance with the Islamic State] will be dealt with according to Islamic law.”16 A second report in November 2015 noted that al-Shabaab radio stations issued a threat to members who were thinking about joining the Islamic State.17 “If anyone says he belongs to another Islamic movement [other than that of al-Qa`ida], kill him on the spot … we will cut the throat of anyone … if they undermine unity.” These releases coincided with others by al-Shabaab’s spokesman Ali Mahmud Rage, which warned al-Shabaab members about advocating an alliance with the Islamic State, suggesting that those who sought to promote division within al-Shabaab are “infidels” and will be “burnt in hell.”18

Beyond issuing statements prohibiting pro-Islamic State sentiments, al-Shabaab—led by its notorious internal security service, the Amniyat—moved against its own members who sympathized with the group. Soon after the overtures from the Islamic State began, in September 2015, al-Shabaab arrested five of its own pro-Islamic State members in Jamame, a town in the Lower Jubba Region.19 In October 2015, the Amniyat arrested at least 30 more pro-Islamic State al-Shabaab fighters.20 A month later in November 2015, al-Shabaab executed five former leaders of the group, including Hussein Abdi Gedi, who was formerly al-Shabaab’s deputy emir for the Middle Jubba Region but who had recently become the leader of a small pro-Islamic State faction based there.21 Later in November 2015, the Amniyat initiated large-scale arrests of al-Shabaab members with Islamic State sympathies across southern Somalia in the towns of Jilib, Saakow, Jamame, Hagar, and Qunyo Barrow,22 including some foreign fighters from Egypt and Morocco. Fast forward to late March 2017, and al-Shabaab reportedly executed at least five Kenyan members of the group for pledging allegiance to the Islamic State in the Hiraan region, and a month later, two prominent al-Shabaab commanders, Said Bubul and Abdul Karim, were also executed for switching their allegiances.23

Phase 4: Al-Shabaab Attacks Somali-Based Islamic State Cells

The fourth phase of the clash between al-Shabaab and the Islamic State in Somalia began in November 2015, when the discord between the groups went from the online sphere to physical attacks. There are at least four instances in which al-Shabaab has attacked avowed Islamic State personnel. The first occurred in November 2015, when al-Shabaab’s Amniyat clashed with an Islamic State cell in southern Somalia led by Bashir Abu Numan.d The skirmish near the town of Saakow in the Middle Jubba region left eight militants dead, including Numan.24 The second al-Shabaab attack on Islamic State members occurred in December 2015, when the Amniyat killed several members of another ISS faction in southern Somalia, including Mohammad Makkawi Ibrahim, a former member of al-Qa`ida in Sudan linked to a 2008 assassination of a USAID employee in Khartoum.25 The third instance was a skirmish between al-Shabaab fighters and Mumin’s faction in Puntland, though the number of casualties remains unclear. The fourth instance of an al-Shabaab attack on an Islamic State faction occurred a few weeks later in late December 2015 when the Amniyat battled an Islamic State faction in Qunyo Barrow, in the Lower Shabelle region.26

A few points bear stating before moving forward. First, it is important to note that the violence between al-Shabaab and Islamic State cells has been unidirectional: al-Shabaab has only attacked Islamic State cells. To date, the authors have not found evidence of either northern or southern Islamic State cells in Somalia attempting to attack al-Shabaab. Second, the majority of the battles between al-Shabaab and the Islamic State have been between al-Shabaab and non-Mumin ISS cells in southern Somalia. Again, although Mumin’s ISS is the stronger of the two Islamic State affiliate groups in Somalia, its relative distance from al-Shabaab’s areas of operation means that the two clash less frequently than the southern Islamic State factions. As per the above, the authors have found evidence of only one clash so far between al-Shabaab and Mumin’s faction in northern Somalia.27 Third, it is worth noting that other actors in Somalia, especially the Ahlu Sunnah wal Jamaa (ASWJ) coalition of anti-al-Shabaab clans have also claimed to have arrested and even physically fought against pro-Islamic State fighters in central Somalia last year, while Somali officials have also claimed that fighting occurred last year in the Bay and Lower Shabelle regions between Somali and pro-Islamic State forces.28

The Islamic State Challenge to al-Shabaab

Having described the conflict between the various Islamic State cells in Somalia, this article now looks at the extent these upstart Islamic State cells challenge al-Shabaab’s prolonged hegemony as Somalia’s preeminent jihadi group. It is useful to examine this from three dimensions: capacity for violence, capability for governance, and propaganda efforts.

Assessing ISS vs. al-Shabaab on Violence

In considering capacity for violence, a key determinant is how many fighters each group has. When Mumin first defected from al-Shabaab to form the Islamic State in Somalia, initial reports suggested that only 20 of the 300 al-Shabaab fighters from his al-Shabaab cell in Somalia’s northern autonomous Puntland region decided to leave with him.e Despite this inauspicious beginning, upper estimates suggested that at its peak, the group had at least 200 people.29 However, due to a combination of losses in military operationsf or defections, ISS has remained relatively small. In June 2017, a defector from Mumin’s ISS group reportedly told Puntland authorities that the faction contained only 70 members, almost entirely based in the eastern Bari regionj of the country.30 The defector also claimed that the group was so low on funds and supplies that it often resorts to stealing livestock and food and to extorting locals.31 It is likely that this June 2017 number has risen following increased recruitment efforts in Puntland, the main source of ISS recruiting, given that Puntland is Mumin’s ancestral homeland. Beyond traditional means of recruitment, in the U.S. State Department’s designation of Mumin as a global terrorist, it noted that he had “expanded his cell of Islamic State supporters by kidnapping young boys aged 10 to 15, indoctrinating them, and forcing them to take up militant activity.”32 Beyond soldiers, a former Somali intelligence official also reported last year that Mumin’s faction has received assistance from Islamic State-loyal militants in Yemen. According to this account, in addition to money, weapons, and uniforms, Islamic State militants in Yemen also sent trainers to inspect ISS bases.33 And, a U.N. report released as this piece was going to print, in November 2017, has claimed that Mumin’s faction receives money and guidance from Islamic State officials in Syria and Iraq. However, the authors cannot verify this report.34

The Islamic State-loyal force officially claimed its first attack inside Somalia on April 25, 2016, when the Islamic State-affiliated news outlet Amaq released a statementh claiming that “fighters of the Islamic State” had detonated an IED against an African Union convoy in Mogadishu.35 Unquestionably, however, ISS’ most important attacks occurred on October 26, 2016—nearly a year after its emergence—when Mumin’s forces captured the port town of Qandala after Puntland security forces retreated.36 A video released by Amaq showed a handful of Islamic State fighters parading through the streets and hoisting the Islamic State’s black flag on several rooftops of the town.37 And, while Puntland authorities said a day later that Islamic State forces had left the town, Somali journalists refuted this claim.38 Nevertheless, by December 7, 2016, Puntland forces again reported that its forces had regained control of the town, offering photo evidence and ending ISS’ siege.39 Apart from the Qandala occupation, recent attacks claimed by the Islamic State in Somalia include its first claimed suicide bombing in Bosaso on May 25, 2017,40 and an assault on a hotel in Bosaso on February 8, 2017.41

As an older and more established group, al-Shabaab’s capacity for violence is far more proven than that of ISS. While the exact number of fighters in the ranks of al-Shabaab is very difficult to ascertain, current estimates suggest that al-Shabaab has between 5,000 to 9,000 within its ranks.42 Most of these fighters are native Somalis. Al-Shabaab also contains sizeable portions of fighters from other East African states, such as Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. Arabs and Western fighters have also been documented within al-Shabaab’s ranks, including senior figures.43 Conversely, while ISS does not seem to have a significant number of non-Somalis, the aforementioned U.N. report did note the presence of a senior Sudanese member, as well as some members from Yemen.44

Operationally, al-Shabaab routinely mounts large-scale assaults on Somali government officials and troops, in addition to attacking personnel associated with the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM). Although it has lost considerable territory since the apogee of its operations in 2011, it continues to penetrate more heavily fortified areas of Mogadishu and has also mounted both assaults and suicide bombings outside of Somalia, including in Kenya, Uganda, and Djibouti. In particular, in a forthcoming report, the authors have given acute focus to al-Shabaab’s proclivity for suicide bombings45—documenting at least 214 al-Shabaab suicide bombers since 2006, including the massive October 2017 attack that left an estimated 358 dead and another 400 wounded.46 Indeed, as of late 2017, al-Shabaab was noted for being the deadliest terror group in all of Africa in the new millennium,47 a distinction that the Islamic State in Somalia is far from challenging.

Assessing ISS vs. al-Shabaab on Governance

When it comes to governance, ISS appears to have relatively little capability. Reports of ISS governance are virtually nonexistent. Even when ISS held the town of Qandala in October 2016, there was no evidence ISS made a real attempt at governing.i Especially given that civilians of Qandala fled during the fighting, this removed the chance of ISS engaging in any form of governance. Its current territorial holdings, thought to be small swaths in the mountainous areas of the Bari region, contain few to no civilians, and the land that the group is assumed to hold is not believed to be very expansive. The nearest suggestion of possible ISS governance comes from an ISS defector, Abdulahi Mohamed Saed, who told Puntland authorities of ISS members engaging in extortion.48 However, this is likely in reference to extortion of civilian populations in ISS’ area of operations generally and not in any direct way in reference to those that it “governs” per se.

For its part, al-Shabaab acts, in many parts of the country, as a full-on stand-in for the state. Among other governance capabilities, in varying locales it provides food, water, and education; runs an effective judiciary; provides security; has an effective tax system; and maintains roads.49 To that end, as of mid-2017, the researcher Tricia Bacon found that “al-Shabab is thriving because it’s still offering a comparatively attractive alternative to the Somali government. It capitalizes on grievances, keeps areas secure and settles disputes, with relatively little corruption.”50

Indeed, whereas ISS’ potential for governance is inherently stunted because of its limited territorial claims, in the case of al-Shabaab, it is precisely because of the wide-ranging territorial presence of the group that capacity for governance is imperative. Primarily situated in the Hiran, Middle Shebelle, Lower Shebelle, Bay, Bakool, Gedo, Lower Juba, and Middle Juba regions in southern Somalia, al-Shabaab maintains a significant presence in central and northern Somalia as well.51 While the group has been forced out of many of its urban strongholds by African Union and Somali forces over the years, it continues to control significant swaths of rural territory in southern and central Somalia.52 In short, whereas there is virtually no evidence that the Islamic State in Somalia engages in any real sort of governance—both out of lack of territorial holding and its small size—for al-Shabaab, one of its primary interpretations of its role in the county is as a stand-in for an impotent state, to include the provision of a wide-range of governmental and social services.

Assessing ISS vs. al-Shabaab on Propaganda

Of all three categories investigated, the Islamic State’s propaganda efforts are the domain in which it is most demonstrably inferior to al-Shabaab. To date, there is no official media wing of the Islamic State in Somalia nor is there a robust informal media presence run by its members or sympathizers. Despite the lack of ISS’ own media capabilities, Islamic State central’s media apparatus—including Amaq—has released photos and videos from Somalia, while other official Islamic State wilayat, as discussed previously, have released videos about or featuring ethnic Somali fighters.k

Conversely, al-Shabaab’s propaganda machine is generally well-run and prolific. Al-Shabaab operates several radio stations in southern Somalia, including Radio Al Furqan and Radio Al Andalus. It frequently produces videos through its Al Kata’ib media wing, and disseminates photo reports on various aspects of its operations published by the websites of its radio stations, Al Furqan and Al Andalus. Since at least 2015, it has also run the Shahada News Agency, which reports on its daily activities and also produces photo reports in a more “traditional” news setting. Al-Shabaab and its supporters also run several Telegram channels, spreading new and archived propaganda in English, Arabic, Somali, and Swahili, and most recently, Oromo.l Every month, al-Shabaab also releases a monthly report of its daily operations around the country. Thus, in the main, al-Shabaab’s myriad media outlets—ranging from radio stations to internet releases propagated both by al-Shabaab members and its adopted parent group, al-Qa`ida—leaves al-Shabaab significantly ahead of the propaganda efforts of its would-be rival, ISS, which has no real parallel capacity of which to speak.

Assessing Future Scenarios

It remains unlikely that the Islamic State in Somalia will imminently challenge al-Shabaab for hegemony, due to a combination of its inferior capabilities in the areas of capacity for violence, ability for governance, and quantity and quality of propaganda. However, under what hypothetical conditions might it be able to do so?

On one hand, there are changes that ISS itself could undertake to make it more competitive. First, at present, the authors see little tangible evidence of real funding of ISS from the Islamic State, apart from some affiliates in Yemen. If for some reason the Islamic State decided to increase funding, ISS could improve its standing vis-à-vis al-Shabaab. Second, at present, foreign fighters seem to be rare in the ranks of ISS: most of its members, as previously stated, are defectors from al-Shabaab, or new recruits from the Puntland region of Somalia. If ISS begins to attract foreign fighters regionally—especially from Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, or Yemen—or globally—especially foreign fighters leaving the crumbling caliphate in the Levant—its growing numbers could allow it to challenge al-Shabaab. Third, another factor that would help ISS to gain prominence would be if it could actually hold territory in a sustained way.

On the other hand, there are missteps that al-Shabaab itself might make that could give ISS an upper hand in the battle for jihadi supremacy. For one, a surge by AMISOM—potentially buoyed by the entrance of more Ethiopian troops in November 201753— and a poor response by al-Shabaab could work to degrade the group, while the weaker and more benign-seeming ISS could theoretically strengthen itself in the relative shadows. Second, it could be the case that the internecine battles within al-Shabaab could lead it to splinter. For instance, commentators have recently noted that there are a range of competing factions within the group—those loyal to al-Qa`ida versus those (quietly) sympathetic to the Islamic State and those who accept foreign fighters into the group’s ranks versus those that do not; and those who believe that the group should ‘liberalize’ versus those who do not.54 However, it remains to be seen how widespread these reported divisions are. Third, for whatever reason, al-Shabaab could begin to fail on the battlefield, losing its leaders (thanks to new broader U.S. mandates for drone targeting),55 failing at governance (with citizens losing patience for overly harsh rule), and losing access to financing (via new embargos on the charcoal trade),56 all of which could exacerbate tensions within the group and lead to fighters’ switching allegiances to ISS.

Finally, there are also scenarios in which al-Shabaab gains even greater power vis-à-vis the upstart Islamic State factions in Somalia. For one, if Mumin or other Islamic State leaders in Somalia are killed, it is a strong possibility that given the small size of the cells and waning fortunes of Islamic State globally, the cells might collapse entirely. With the news that the United States began conducting airstrikes against the Islamic State in Somalia in November 2017, this scenario is not wholly unlikely. If ISS collapsed, fighters from Mumin’s faction could attempt to return to the al-Shabaab fold. How al-Shabaab would react to the repentant soldiers is unclear.

While these possibilities may exist, many of these scenarios are relatively unlikely. Indeed, barring any significant changes, al-Shabaab will face few serious challenges from the Islamic State in Somalia for the foreseeable future. CTC

Jason Warner is an assistant professor in the Department of Social Sciences at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, where he also directs the Africa research profile at the Combating Terrorism Center. Follow @warnjason

Caleb Weiss is a research analyst and contributor to FDD’s Long War Journal where he focuses on violent non-state actors in the Middle East and Africa with a special focus on al-Qa`ida and its branches. Follow @Weissenberg7

Substantive Notes

[a] Mumin was a well-known ideologue who was featured in several al-Shabaab videos, when he was still part of that group. This includes an April 2015 video in which he tried to rally fighters to the Golis Mountains in Somalia’s northern Sanaag Region. Prior to that, he was featured in a video series for Ramadan, one in which he gave a speech. He would appear in at least two more videos documenting al-Shabaab battles in the Lower Shabelle and Bay regions before his defection.

[b] Mumin, Somali by birth, spent time in Sweden and the United Kingdom, where he became known as a radical cleric, before returning to Somalia to fight within al-Shabaab in 2010. While he was originally sent to the Puntland region to attract recruits in 2012, when his commander in the region, Mohamed Said Atom, was given asylum in Qatar, Mumin played an increasingly larger role in the group. For more see, Jason Warner, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Three “New” Islamic State Affiliates,” CTC Sentinel 10:1 (2017); Christopher Anzalone, “The Resilience of al-Shabaab,” CTC Sentinel 9:4 (2016); Christopher Anzalone, “From al-Shabab to the Islamic State: The Bay‘a of ‘Abd al-Qadir Mu’min and Its Implications,” jihadology.net, October 25, 2015.

[c] The exact nature of connections between Mumin and ISS groups in southern Somalia remain unclear. At their deepest, connections could be such that Mumin controls south Islamic State groups, which nevertheless maintain significant autonomy from him. At their most shallow, there might well be only nominal connections between Mumin and southern ISS groups. Another possibility is that, in fact, there are no significant remaining Islamic State elements in southern Somalia at all. Indeed, although there have been claims of attacks, it is unclear if these are legitimate, or simply fabrications.

[d] So important was he to the group that Mumin’s ISS faction is known to have operated a training camp named after Numan.

[e] However, as these numbers are mutable, it could well be the case that more than 20 left with him. For more, see Bill Roggio, “US adds Islamic State commander in Somalia to list of global terrorists,” FDD’s Long War Journal, August 31, 2016.

[f] For instance, Mumin’s faction reportedly lost 30 fighters in the battles at Qandala, according to Harun Maruf. Harun Maruf, “Forces Retake Somali Town Held by Pro-Islamic State Fighters,” VOA News, December 7, 2016.

[g] However, there is some debate as to whether the April 25, 2016, attack was the first conducted by the Islamic State in Somalia or if one preceded it. On December 11, 2015, Somali media reported that pro-Islamic State militants in southern Somalia captured a small town near the border with Kenya. Not long after, Somali officials then claimed that the town was back under government control. However, the official statement did not explicitly mention a pro-Islamic State militant faction, thus raising questions about whether the group was ISS, or perhaps instead al-Shabaab. For more, see Abdirizak Shiino, “Kismaayo: Al-Shabaabka Daacish la midoobey oo qabsadey Tuulo Barwaaqo,” Horseed Media, December 9, 2015, and “Jubba: Tuulo-Barwaaqo Dib Ayaan U Qabsanay,” VOA Somali, December 11, 2015.

[h] This statement was released on the same day a video was disseminated showing a training camp run by Mumin’s forces in Puntland.

[i] The authors have not been able to find any evidence of this taking place.

[j] To date, ISS appears to be almost exclusively centered in the mountainous Bari region of northern Somalia. This concentration in Puntland has been confirmed by the aforementioned June 2017 ISS defector, as well as by release of photos from the Islamic State’s central media office on October 11, 2017, showing Mumin’s ISS troops in terrain that appeared to be the Bari mountains. Giving further credence to the fact that the group is primarily based in Bari, many of the operations of the group take place in Bosaso, the capital of the Bari region.

[k] The Islamic State’s wilayat Furat, Sayna, Homs, Ninewa, Hadramawt, Khayr, West Africa, and Tripoli all released videos from May 2015 to January 2016.

[l] On September 24, 2017, al-Shabaab’s Al Kata’ib Media released an Oromo translation of its video “They Are Not Welcome, They Shall Burn in the Fire,” which was distributed by al-Qa`ida’s Global Islamic Media Front.

Citations

[1] See Conor Gaffey, “ISIS Claims Somali Suicide Attack as It Vies with Al-Shabaab for Recognition,” Newsweek, May 24, 2017; Aislinn Laing, “How al-Qaeda and Islamic State are competing for al-Shabaab in Somalia,” Telegraph, January 12, 2016; Heidi Vogt, “Islamic State in Africa Tries to Lure Members From al-Shabaab,” Wall Street Journal, October 26, 2016; Alex Dick Godfrey, “Al-Shabab and Islamic State: A Rivalry in East Africa,” National Interest, January 28, 2016; Omar S Mahmood, “Does the Islamic State threaten al-Shabaab’s hegemony in Somalia?” Institute for Security Studies, November 21, 2016; and Marco Cochi, “The growing threat of Islamic State in Somalia,” East West, May 26, 2017.

[2] Stig Jarle Hansen, Al-Shabaab in Somalia: The History and Ideology of a Militant Islamist Group, 2005-2012 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

[3] Hamil al-Bushra, “Somalia of the Caliphate and Combat: A Message to Our People in Somalia,” “Somal al-Khilafah wal-Nizal: Risalah ila Ahlina fi al-Somal,” “Al-Jabha al-I`lamiyyah li-Nusrat al-Dawla al-Islamiyyah,” February 24, 2015, available at https://justpaste.it/hamilbushra-19.

[4] Al-Hurr al-Balqani, “You Turned Your Backs to It?” “Awlaytumuha Zuhurakum?” “Mu’asasat al-Battar al-I`lamiyyah,” September 23, 2015, available at https://justpate.it/urwm.

[5] Abu Rida al-Sunni, “A Call to the Mujahidin of Somalia,” “Nida’ ila Mujahidi al-Somal,” “Mu’asasat al-Wafaa lil-Intaj al-I`lami,” September 29, 2015.

[6] Al-Bushra.

[7] “O Mujahid in the Land of Somalia, Hear from Us,” “Ima` Minna Ayuha al-Mujahid fi Ard al-Somal,” Wilayat Ninawa Media Office, October 1, 2015.

[8] “A Message to the Mujahidin in the Land of Somalia,” “Risalah lil-Mujahidin fi Ard al-Somal,” Wilayat Homs Media Office, October 1, 2015.

[9] “From Sinai to Somalia,” “Min Sina’ ila al-Somal,” Wilayat Sinai Media Office, October 1, 2015.

[10] “Join the Caravan,” “Ilhaq bil-Qafilah,” Wilayat al-Raqqa Media Office, October 2, 2015.

[11] “From the Land of the Levant to the Mujahidin in Somalia,” “Min Ard al-Sham ila al-Mujahidin fi al-Somal,” Wilayat al-Baraka Media Office, October 4, 2015.

[12] “The Islamic State and the Shabab Movement: Which One is the Suppressed One?” “al-Dawla al-Islamiyyah wa-Harakat al-Shabab: man al-Mazlum Minhuma Ya-Tara?” Abu Maysarah al-Somali, October 27, 2015, available at https://justpaste.it/25400.

[13] Anzalone, “The Resilience of al-Shabaab.”

[14] Jason Warner, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Three “New” Islamic State Affiliates,” CTC Sentinel 10:1 (2017).

[15] Anzalone, “The Resilience of al-Shabaab.”

[16] Harun Maruf, “Al-Qaida or Islamic State? Issue Simmers Within Al-Shabab,” VOA News, September 30, 2015.

[17] “Somalia’s Al Qaeda Branch Warns Members from Joining Islamic State,” Wacaal, November 2015.

[18] Thomas Joscelyn, “American jihadist reportedly flees al Qaeda’s crackdown in Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, December 8, 2015.

[19] Maruf, “Al-Qaida or Islamic State? Issue Simmers Within Al-Shabab.”

[20] “Al-Shabab Oo Xirtay 30 Ajaaniib & Soomaali ah,” VOA Somali, October 14, 2015.

[21] “Revealed Names of Pro ISIL Shabaab Members Executed in Middle Jubba Region,” Wacaal, November 2015.

[22] Harun Maruf, “Al-Shabab make new arrests in towns of Jillib Saakow,Jamame, Hagar, Kunyo Barrow of members suspected of having links with ISIS: reports,” Twitter, November 18, 2016.

[23] Fred Mukinda, “Al-Qaeda or ISIS? Shabaab militants fight,” Daily Nation, April 23, 2017.

[24] Harun Maruf, “Al-Shabab Official Threatens Pro-Islamic State Fighters,” VOA News, November 24, 2015.

[25] “Sudanese USAID employee assassin killed by al-Shabaab in Somalia,” Sudan Tribune, December 6, 2015.

[26] Somalia Newsroom, “Wow: In the last week, #Somalia’s Kunyo Barrow area saw #Shabaab killing pro-#ISIS elements AND U.S. air strikes.” Twitter, December 7, 2015.

[27] “Al-Shabaab Fighters Clash Over ISIS Allegiance in Puntland,” Somalia Newsroom, December 25, 2015.

[28] “Somali Authorities Display Pro-ISIS Militants Rounded Up in Baidoa,” Somalia Newsroom, September 2, 2016; Harun Maruf, “Intelligence Official: Islamic State Growing in Somalia,” VOA News, May 5, 2016.

[29] Harun Maruf, “Somali Officials Vow to Retake Puntland Town,” VOA News, October 28, 2016.

[30] “Somalia: ISIS fighter surrenders to Puntland authorities,” Garowe Online, June 6, 2017.

[31] Ibid.

[32] “State Department Terrorist Designation of Abdiqadir Mumin,” U.S. State Department, August 31, 2016.

[33] Maruf, “Intelligence Official: Islamic State Growing in Somalia.”

[34] Katharine Houreld, “Islamic State’s footprint spreading in northern Somalia: U.N.,” Reuters, November 8, 2017.

[35] Bill Roggio and Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State highlights ‘first camp of the Caliphate in Somalia,’” FDD’s Long War Journal, April 25, 2016.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State fighters withdraw from captured Somali port town,” FDD’s Long War Journal, October 28, 2016.

[38] Harun Maruf, “Qandala dairy: It’s day 9 of pro-IS militant control in Qandala; Puntland promised a big offensive but some say too late to curtail threat.” Twitter, November 2, 2016.

[39] Maruf, “Forces Retake Somali Town Held by Pro-Islamic State Fighters.”

[40] Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State claims suicide bombing in Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, May 25, 2017.

[41] Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State claims hotel attack in northern Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, February 9, 2017.

[42] Country Policy and Information Note 2017, p. 10.

[43] Bill Roggio, “US adds American, Kenyan Shabaab leaders to list of designated terrorists,” FDD’s Long War Journal, July 31, 2011; Bill Roggio, “American al Qaeda operative distributes aid at Somali relief camp,” FDD’s Long War Journal, October 14, 2011.

[44] Houreld, November 8, 2017.

[45] Jason Warner, Ellen Chapin, and Caleb Weiss, Understanding al-Shabaab’s Suicide Bombers (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, forthcoming 2018).

[46] “Mogadishu bombing death toll rises to 358,” Al Jazeera, October 20, 2017.

[47] Conor Gaffey, “How Al Shabaab Overtook Boko Haram to Become Africa’s Deadliest Militants,” Newsweek, June 2, 2017.

[48] “Somalia: ISIS fighter surrenders to Puntland authorities.”

[49] Tricia Bacon, “This Is Why Al-Shabaab Won’t Be Going Away Anytime Soon,” Washington Post, July 6, 2017; Anzalone, “The Resilience of al-Shabaab.”

[50] Ibid.

[51] Stig Hansen, “Somalia: Why a ‘Semi-Territorial’ al-Shabaab Remains a Threat,” Newsweek, October 19, 2016.

[52] Ibid.

[53] “Ethiopia Deploys 1000 Troops to Somalia,” Ezega, November 4, 2017.

[54] Dominic Wabala, “Three Kenyan Fighters Executed by Al Shabaab,” Standard, September 24, 2017.

[55] Charlie Savage and Eric Schmitt, “Trump Poised to Drop Some Limits on Drone Strikes and Commando Raids,” New York Times, September 21, 2017.

[56] “Security Council Considers Illicit Charcoal Trade in Somalia, Tensions over Mineral Resources, Eritrea Actions on Issue of Djibouti War Prisoners,” United Nations, February 18, 2016.

Skip to content

Skip to content