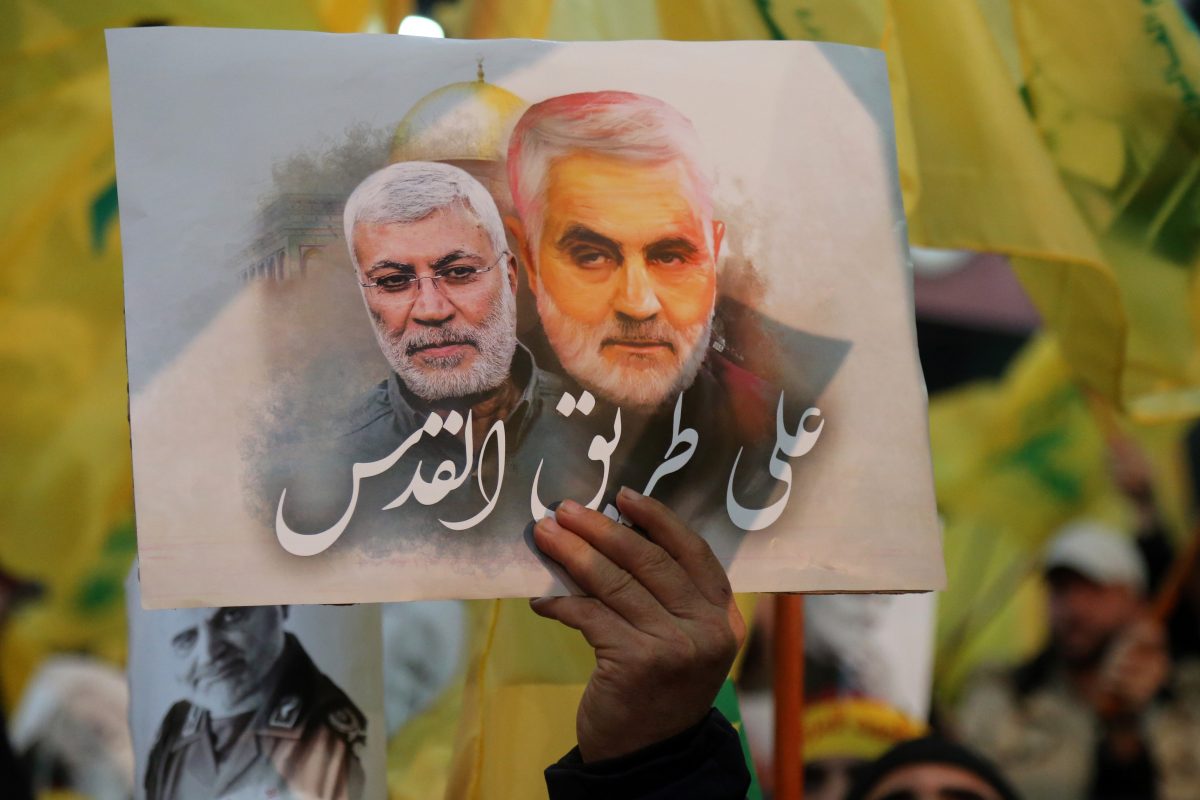

Abstract: The threats to U.S. interests in the Middle East, and possibly in the U.S. homeland, increased in the wake of the January 3, 2020, U.S. drone strike that killed Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force chief General Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi Shi`a militia commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis. While the primary overt objective of Iran and its proxies post-Soleimani will likely be to push all U.S. military forces out of Iraq and the region, they will undoubtedly also want to avenge Soleimani’s death. And as Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has made clear, all Iranian proxy militant groups will be expected to play their parts in this campaign. When they do, Iran and the foreign legion of Shi`a proxies at its disposal are likely to employ new types of operational tradecraft, including deploying cells comprised of operatives from various proxy groups and potentially even doing something authorities worry about but have never seen to date, namely encouraging Shi`a homegrown violent extremist terrorist attacks.

Speaking in the wake of the January 3, 2020, U.S. drone strike in Baghdad that killed the commander of Iran’s Quds Force, Major General Qassem Soleimani, Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah made clear that the response to the Soleimani assassination would be carried out by the full range of Shi`a militant groups beholden to Iran far into the future.1 In the post-Soleimani era, Nasrallah intimated, operations by Iran and its web of proxy groups would also deviate from traditional tactics. “Whoever thinks that this dear martyrdom will be forgotten is mistaken, and we are approaching a new era,” he said.2

To be sure, much of the established modus operandi honed over years of training and practice by the Quds Force and Hezbollah will continue to feature prominently in Iranian and Iranian proxy operations.3 But Nasrallah’s vague pledge to modernize begs the question: What might be expected of a “new era” of international operations carried out by Iran and its proxy forces?

One difference from past operations is opportunistic—prioritizing the effort to push U.S. forces out of the Middle East. Iran will likely leverage Soleimani’s assassination to achieve with his death what he aspired toward but failed to achieve in life. Another departure is more strategic— further solidifying the network of Shi`a militant groups Soleimani quilted together under the Quds Force. Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has described the Quds Force as Tehran’s “fighters without borders,” but given the Quds Force’s control of this network of Shi`a foreign fighters, the term more aptly applies to the Quds Force and the Shi`a militant networks under its control.4 Hezbollah has already stepped in to help guide Iraq’s various Shi`a militias, at least temporarily.5 Other changes will likely be tactical, increasingly focused on trying to enhance operational security and the potential to carry out terrorist operations with reasonable deniability.

This article focuses on the areas of tactical adjustment that the Quds Force, Hezbollah, and other Shi`a militant groups might make to enhance their international terrorist attack capabilities. First, the article explains why U.S. authorities are so animated by the potential threat of a terrorist attack against U.S. interests, possibly in the homeland, following the Soleimani drone strike. Second, it forecasts and assesses in turn two specific lines of operational effort that authorities fear Iran and its proxies (led by the Quds Force and Hezbollah) are developing for future operations:

(a) Deploying teams including non-Iranian and non-Lebanese Shi`a militants from around the world and representing a variety of Iranian proxy groups to carry out international terror operations at Iran’s behest; and

(b) Developing and encouraging a terrorist trend common in the world of Sunni extremism but not yet seen in the context of Shi`a extremism—Shi`a homegrown violent extremism (HVE).

The Threat to the United States

U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies long assessed that Iran and its proxy groups were unlikely to carry out an attack in the U.S. homeland, unless the United States took direct action undermining their interests.

For example, a 1994 FBI report, issued in the wake of the Hezbollah bombing targeting the AMIA Jewish community center in Buenos Aires a few months earlier, downplayed the likelihood of Hezbollah attacking U.S. interests, unless the United States took actions directly threatening Hezbollah. “The Hezbollah leadership, based in Beirut, Lebanon, would be reluctant to jeopardize the relatively safe environment its members enjoy in the United States by committing a terrorist act within the U.S. borders,” it assessed. “However, such a decision could be initiated in reaction to a perceived threat from the United States or its allies against Hezbollah interests.”6

In 2002, the FBI informed the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that while “many Hezbollah subjects based in the United States have the capability to attempt terrorist attacks here should this be the desired objective of the group,” Hezbollah had never carried out an attack in the United States and its extensive fundraising activities in the United States would likely serve as a disincentive for simultaneous operational activities.7

But over the past few years, well before the Soleimani hit, authorities disrupted Iranian and Hezbollah operations here in the United States that have forced them to reconsider longstanding assessments of the possibility that either a state or non-state group might seriously consider carrying out an attack in the homeland.8

In fact, in 2012, Iranian-American used car salesman Mansour Arbabsiar pleaded guilty to plotting the previous year with Iranian agents to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States in Washington, D.C.9 This was not the first time Iran plotted an attack in the United States, but it was the most spectacular and came at a time when few analysts assessed Iran would consider such an operation.10 In the wake of that case, then Director of National Intelligence James Clapper testified before Congress that the plot “shows that some Iranian officials—probably including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei—have changed their calculus and are now more willing to conduct an attack in the United States in response to real or perceived U.S. actions that threaten the regime.”11

U.S. officials further worried that Hezbollah’s calculus may have begun to shift in early 2015, when it became a matter of public record that the February 2008 assassination of Imad Mughniyeh, the founding leader of Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad Organization terrorist network, was a joint U.S.-Israeli operation.12 Hezbollah printed a deck of playing cards featuring Israeli leaders it held responsible for Mughniyeh’s death, which some described as a hit list.13 Might Hezbollah now seek to avenge Mughniyeh’s death by attacking American officials too? As Matthew Olsen, the director of the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) at the time, testified just five months before Mughniyeh was killed: “Lebanese Hezbollah remains committed to conducting terrorist activities worldwide. … We remain concerned the group’s activities could either endanger or target U.S. and other Western interests.”14

Then, in June 2017, the FBI arrested two alleged Hezbollah operatives, Ali Kourani and Samer El Debek, for carrying out surveillance of U.S. targets in the United States.15 “While living in the United States, Kourani served as an operative of Hezbollah in order to help the foreign terrorist organization prepare for potential future attacks against the United States,” U.S. Assistant Attorney General for National Security John C. Demers said. These included buildings housing the FBI and U.S. Secret Service in Manhattan, as well as New York’s JFK airport and a U.S. Army Armory. Kourani was tried, convicted, and sentenced to 40 years.16 El Debek has yet to stand trial.

Four months after the arrests, in October 2017, then director of NCTC Nicholas Rasmussen told reporters that Hezbollah was “determined to give itself a potential [U.S.] homeland option as a critical component of its terrorism playbook.” “This is something that those of us in the counter-terrorism community take very, very seriously,” he added.17

Kourani described himself as a Hezbollah sleeper agent. According to the FBI, Kourani informed that “there would be certain scenarios that would require action or conduct by those who belonged to the cell.” Kourani reported Hezbollah operatives like him would be called upon to act in the event that the United States and Iran went to war, or if the United States were to take certain unnamed actions targeting Hezbollah, Nasrallah himself, or Iranian interests. Kourani added that “in those scenarios the sleeper cell would also be triggered into action.”18

In September 2019, the FBI arrested Ali Saab, an alleged Hezbollah operative who underwent military and bomb-making training in Lebanon and later collected intelligence on potential targets in New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. Saab allegedly provided details on targets including the United Nations headquarters, Statue of Liberty, and New York airports, tunnels, and bridges—including detailed photographs and notes on structural weaknesses and “soft spots” for potential Hezbollah targets “in order to determine how a future attack could cause the most destruction,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice.19 Saab has yet to stand trial.

The U.S. assassination of Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis (aka Jamal Jaafar Ibrahimi), the leader of the Iraqi Shi`a militant group Kata’ib Hezbollah who was with Soleimani at the time, appears to meet the standard Kourani described for potential Hezbollah terrorist action, namely U.S. action directly targeting a senior Iranian official, according to the assessment of this author. As such, it is not surprising that in the wake of the Soleimani assassination, Hezbollah’s threat rhetoric took a sudden and sharp shift away from focusing primarily on Israeli targets. “America is the number one threat,” Nasrallah announced after the drone strike that killed Soleimani, adding that “Israel is just a military tool or base.”20

It seems clear that the primary overt objective of Iran and its proxies post-Soleimani will be to push all U.S. military forces out of Iraq and out of the Middle East. Nasrallah made this clear, warning that this included “the U.S. military bases, the U.S. warships, every single U.S. officer and soldier in our region, in our countries and on our territories.”21 And he intimated at how Hezbollah could help evict U.S. forces from the region, boasting that “[t]he suicide attackers who forced the Americans to leave from our region in the past are still here and their numbers have increased.”22

While stating that his threats did not apply to American civilians in the region, Nasrallah warned that when it came to U.S. soldiers and officials, “the only alternative for them to be leaving horizontally [in coffins] is for them to leave vertically, on their own.”23

Iran and its proxies will also want to avenge Soleimani’s death, possibly by targeting a senior U.S. official in response to the assassination of one of their own (an option Nasrallah has publicly downplayed)24 or by executing some other type of reasonably deniable asymmetric attack.

Indeed, deniability is also important politically. Iran and its proxies will want to be especially careful not to be tied to any action that might stem the flow of anti-American momentum Tehran feels it has at its back, in Iraq in particular, following the Soleimani strike. Neither Iran nor Hezbollah wants direct conflict with the United States,a and in the wake of the Soleimani hit, they have to take seriously U.S. threats to retaliate harshly for any attack on American citizens.b

U.S. law enforcement and intelligence fear Iran and its proxies may well decide to carry out a terrorist attack to avenge the Soleimani strike, a fact which explains why the day after the strike, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued a bulletin under its National Terrorism Advisory System warning that “Iran likely views terrorist activities as an option to deter or retaliate against its perceived adversaries. In many instances, Iran has targeted United States interests through its partners such as Hezbollah.”25 Following the January 8, 2020, Iranian missile attack on military bases used by U.S. forces in Iraq, former FBI deputy director Andrew McCabe warned of the potential for terrorist attacks by Iran and its proxies—even in the U.S. homeland—in a Washington Post editorial entitled “If you think Iran is done retaliating, think again.”26

One consequence of the Soleimani assassination may be a weakening of Iranian command and control over its various proxies, which were never a uniform bloc of groups equally committed to taking orders from Tehran to begin with.27 But even among those groups most closely aligned with the Quds Force, like Lebanese Hezbollah and Kata’ib Hezbollah in Iraq, the loss of Soleimani—a charismatic leader beloved by Shi`a militia foot soldiers and commanders alike—means the Quds Force is now likely to be run by committee with a few more senior commanders and experienced managers collectively trying to take on the many roles previously filled singularly by Soleimani.28 Soleimani played a hands-on role, involving himself personally in key operations, building rapport and personal bonds with militia commanders, and mediating disputes over prestige or money when those arose among Khamenei’s fighters without borders.29 Lacking the personal touch Soleimani contributed to the command and control of these groups, it is not clear that even if Iran wanted to stop one of its proxy groups from carrying out a terrorist attack it would be in a position to do so. Kata’ib Hezbollah, in particular, is likely to seek vengeance for the assassination of its leader, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, whose intimate ties to the Quds Force and Hezbollah go back decades.30

The International Terror Threat from Iran’s Shi`a Liberation Army

All this begs the question: what might a “new era” of international terror operations carried out by Iran’s “fighters without borders” look like?

A series of arrests of Hezbollah operatives around the world over the past few years—including the three U.S. cases noted above and others in Cyprus, Thailand, France, and Peru—collectively exposed a significant amount of information on the modus operandi of Hezbollah’s covert operations.31 But these cases, some of which only came to light recently, are most revealing about how Hezbollah operated a decade ago, when the operational activities largely took place.

Iranian agents and Hezbollah operatives will undoubtedly play central roles in this new strategy, but they will not, according to the aspirations of Hezbollah’s leader, be acting alone. “Meting out the appropriate punishment to these criminal assassins … will be the responsibility and task of all resistance fighters worldwide,” Nasrallah said on January 3, 2020, shortly after the Soleimani strike. “We will carry a flag on all battlefields and all fronts and we will step up the victories of the axis of resistance with the blessing of his [Soleimani’s] pure blood,” he added.32

One option law enforcement officials assess the Quds Force, Hezbollah, and other elements of Iran’s threat network could employ would be to draw upon the deep bench of Shi`a militants across the spectrum of Iran’s Shi`a proxy groups to carry out terrorist operations. There is ample literature discussing Iran’s ability to deploy Shi`a militia fighters to other battlefields in the region,33 but this new concern focuses on Iran’s ability to deploy select Shi`a militia operatives not to fight in other regional conflicts but to carry out acts of international terrorism.

In a Joint Intelligence Bulletin issued days after Soleimani was killed, the U.S. intelligence community warned that if Iran decided to carry out a retaliatory attack in the United States, it “could act directly or enlist the cooperation of proxies and partners [emphasis added by the author], such as Lebanese Hizbollah.”34

Security officials worry that the next “Hezbollah” attack in the West, or infiltration across Israel’s northern border, could be carried out by non-Iranian, non-Lebanese operatives within these proxy and partners groups from Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Gulf States, or elsewhere. As Nasrallah himself said in a speech following Soleimani’s death, “the rest of the Axis of Resistance must begin operations,” implying that the burden of exacting a price for the Soleimani assassination cannot be carried by Hezbollah alone.35

Hezbollah trained many of these Shi`a militants in the first place, typically in training sessions lasting 20-45 days (though some received additional specialized training), and then fought with them on the battlefield in Syria.36 The Quds Force and Hezbollah are well-placed to spot exceptional candidates, provide them specialized training in terrorist tactics and operational security, and dispatch them to carry out attacks in an effort to hide their own ties to such actions. This may create dangers for Americans on U.S. soil and overseas. The NCTC reported in October 2019, “Iran and Hezbollah’s ongoing efforts to expand their already robust global networks also threaten the homeland.”37 Outside the United States, through the Quds Force and Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), Iran also “maintains links to terrorist operatives and networks in Europe, Asia and Africa that could be called upon to target U.S. or allied personnel.”38

In 2016, an IRGC general first used the term “Shi`a Liberation Army” in reference to the Fatemiyoun brigade of Afghan Shi`a militants fighting on Iran’s behalf in Syria. “The upside of the recent [conflicts] has been the mobilization of a force of nearly 200,000 armed youths in different countries in the region,” the commander of the IRGC said that same year.39 Soleimani invested much time and effort building up and coordinating the mix of Shi`a violent extremist groups, which, despite having their own identities and local grievances, have bonded together in an informal web of relationships serving as proxy agents for Iran. U.S. officials often refer to this as the Iran Threat Network, or ITN.

Syria served not only as an operational training ground but as a finishing school for operational tradecraft for this Shi`a foreign legion, providing Iran a deep bench of experienced militants from among whom it could spot potential candidates for terrorist operations training. Even just a few years ago, until the wars in Syria and Iraq, Iran had no such option. As Colin Clarke and Phillip Smyth noted in November 2017:

The wars in Syria and Iraq have given Iran the opportunity to formalize and expand networks of Shi`a foreign fighters throughout the region. Units of Shi`a militants from Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq are undergoing a transformation into a “Hezbollah”-style organization that is loyal to Iran and willing to fight alongside Iranian troops and advisers. Meanwhile, Afghan and Pakistani Khomeinist networks have been reformed to supply thousands of fighters who can be used as shock troops on battlefields stretching from the Middle East to South Asia.40

To be sure, the U.S. intelligence community has given considerable attention to Iran’s proxy relationships. In November 2019, for example, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) released a report entitled Iran Military Power: Ensuring Regime Survival and Securing Regional Dominance. According to the report,

Through the IRGC-QF, Iran provides its partners, proxies, and affiliates with varying levels of financial assistance, training and materiel support. Iran uses these groups to further its national security objectives while obfuscating Iranian involvement in foreign conflicts. Tehran also relies on them as a means to carry out retaliatory attacks on its adversaries. Most of these groups share similar religious and ideological values with Iran, particularly devotion to Shia Islam and, in some cases, adherence to velayat-e faqih [Rule of the Jurisprudent].41

The support Tehran provides these groups includes “facilitating terrorist attacks,” the DIA reported. “These partner and proxy groups provide Iran with a degree of plausible deniability, and their demonstrated capabilities and willingness to attack Iran’s enemies serve as an additional deterrent.”42 The DIA assessed in late 2019 that “Tehran is likely to continue using these fighters in Syria,” but added that “it remains unclear if there are plans to deploy them to other locations.”43

Whether or not Iran decides to dispatch Afghan Fatemiyoun, Pakistani Zainabiyoun, or Iraqi Heidariyun Shi`a militantsc to other regional battlefronts such as Israel’s norther border or Yemen, it could select the crème de la crème from these militias for specialized terrorist operations training, much as Hezbollah has handpicked militia fighters for its Islamic Jihad Organization terrorist operations.44 As a report by the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London noted, “an essential function that Hizballah has performed on behalf of Iran in the management and mentoring of many of Tehran’s Arab partners. Indeed, the organization has become a central interlocutor for an array of Arab militias and political parties that have sectarian and ideological, or simply opportunistic, ties to Tehran.”45 Today, Hezbollah performs such a function for a wider spectrum of Shi`a militant groups beholden to Iran, such as the Shi`a militia groups in Iraq.46 d

To a significant degree, deploying terrorist attack cells with personnel drawn from various components of Iran’s network of proxies would mark a return to old tradecraft. Consider, for example, the Iranian-directed plots targeting Kuwait in the mid-1980s. The first in this string of attacks were the December 12, 1983, bombings at the American and French embassies in Kuwait, at the Kuwaiti airport, near the American Raytheon Corporation’s grounds, at a Kuwait National Petroleum Company oil rig, and at a government-owned power-station. A seventh bomb, outside a post office, was diffused.47 Six people were killed, and some 87 were injured in the attacks.48 The string of well-coordinated bombings, which occurred within a span of two hours, were executed at Iran’s behest by Lebanese and Iraqi Shi`a militants—including Lebanese Hezbollah’s Mustapha Badreddine and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, then of the Iraqi Dawa Partye (who, according to the United States and Kuwait, helped plan the Kuwait attacks49 and, as already outlined, was killed in January 2020 alongside Soleimani). The nature of the attack provided Iran grounds for plausible deniability. Iran denied any involvement in the plots, insisting that “attribution of these attacks to Iran is part and parcel of a comprehensive plot by the United States of America and its agents against the Islamic revolution.”50

Iran has already found creative new ways to use its Shi`a militia proxies for unorthodox purposes, such as deploying Shi`a fighters to break up anti-regime demonstrations in Iran in November 2019.51 The month before, Iran-backed militia snipers were deployed to Baghdad during anti-government protests there.52

And there is already evidence that Iran and Hezbollah have been moving in this direction. For several years now, Hezbollah has been actively recruiting and deploying dual-nationals—from the United States, Canada, France, Sweden, Great Britain, and Australia, among other countries—who are able to travel for operational purposes on their non-Lebanese passports.53 For example, Ali Kourani traveled from New York to China on his U.S. passport to negotiate a deal to buy ammonium-nitrate ice packs of the kind Hezbollah uses to construct bombs.54 And Samer El Debek allegedly traveled to Thailand to remove explosive precursor materials from a compromised Hezbollah safe house, and to Panama where he allegedly conducted preoperational surveillance of American, Israeli, and Panamanian targets.55

More recently, an article in Le Figaro reported that Hezbollah has begun recruiting operatives with non-Lebanese profiles in the wake of exposures of its Lebanese operatives traveling on non-Lebanese passports. According to this report, in August 2019, a Pakistani suspected of being a Hezbollah operative was questioned by authorities in Thailand. Dozens of operatives with non-Lebanese profiles, including Shi`a from Pakistan and Afghanistan, have been recruited by Hezbollah for foreign operations, and are often deployed using cover stories as tourists, the report stated.56 Another cover involves recruiting Lebanese who have lived somewhere abroad for a long time. In July 2019, Ugandan authorities arrested a Lebanese national who had lived in the country since 2010 on suspicion of being an undercover Hezbollah agent.57

Again, there is precedent for Hezbollah recruiting non-Lebanese operatives. According to a 1994 FBI report, “an Iraqi-born Shia cleric, who is based in Texas, has positioned himself in a leadership role of Hezbollah in the United States.”58

The Quds Force has also begun to recruit non-Iranian Shi`a operatives for espionage and terrorist missions abroad. In January 2019, German authorities arrested a dual Afghan-German citizen, who worked as a translator and advisor for the German army, on charges of spying for Iran.59 In another case, Dutch authorities accused Iran of hiring local criminals to assassinate Iranian dissidents in the Netherlands.60 And in December 2019, a Swedish court convicted an Iraqi man on charges of spying for Iran, including “gathering information on Iranian refugees in Sweden, Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands.”61 Iran recruited an African rebel to build up pro-Iranian terror cells in Central Africa,62 and in June 2019, Israeli authorities arrested a Jordanian national on espionage charges for trying to recruit people in the West Bank to spy on Israel for Iran.63

By deploying members of its foreign legion of proxy groups, its “fighters without borders,” Iran (and Hezbollah) seeks “to anonymize its action in order to conduct its operations without being directly implicated.”64 To that end, authorities are concerned about another possible new trend in Iran Threat Network mobilization—one that to date has never occurred, but nonetheless has the attention of U.S. officials.

Inspiring Lone Offenders: Shi`a HVE?

Testifying before the House Judiciary Committee on February 5, 2020, FBI Director Christopher Wray underscored that the international terrorist threat to the United States had “expanded from sophisticated, externally directed FTO [foreign terrorist organization] plots to include individual attacks carried out by HVE [homegrown violent extremists] who are inspired by designated terrorist organizations.”65 These lone offenders present unique challenges to law enforcement, due to their lack of ties to known terrorists, easy access to extremist material online, ability to radicalize and mobilize to violence quickly, and use of everyday communication platforms that utilize end-to-end encryption. While Director Wray highlighted the particular success the Islamic State has demonstrated in leveraging digital communications to draw lone offenders to its ideology, he noted that many other terrorist organizations reach out to people who may be “susceptible and sympathetic to violent terrorist messages.” In fact, law enforcement agencies are confronting “a surge in terrorist propaganda and training available via the Internet and social media.”66

Today, Iran’s Quds Force and other Shi`a extremist terrorist groups are disseminating extremist material online. This trend has the attention of U.S. law enforcement and intelligence officials, who have warned that one possible “catalyzing event” for Shi`a HVE plotting in the United States would be if “radicalizing enablers” began actively “amplifying anti-US and pro-Shia rhetoric among audiences in the US.”67

Indeed, within 24 hours of the Soleimani drone strike, DHS released a bulletin under its National Terrorism Advisory System warning of potential Iranian or Iranian-inspired plots against the homeland. The bulletin stressed the Department had no information regarding any specific, credible threat to the homeland, but advised that “Homegrown Violent Extremists could capitalize on the heightened tensions to launch individual attacks,” adding that “an attack in the homeland may come with little or no warning.”68

A few days later, DHS, FBI, and NCTC released a joint intelligence bulletin advising federal, state, local, and other counterterrorism and law enforcement officials and private sector partners “to remain vigilant in the event of a potential [Government of Iran] GOI-directed or violent extremist GOI supporter threat to US-based individuals, facilities, and [computer] networks” [emphasis added by the author].69 The report warned not only of Iranian-directed plots—including both lethal attacks and cyber operations—but also of attacks by supporters of Iran inspired to carry out attacks on their own.

Concern within the U.S. counterterrorism community over the prospect of Shi`a HVE attacks predates the Soleimani strike. The intelligence community has given the prospect of Shi`a HVE violence some thought, and NCTC defines Shi`a HVEs as “individuals who are inspired or influenced by state actors such as Iran, foreign terrorist organizations such as Hezbollah, or Shia militant groups but who do not belong to these groups and are not directed by them.”70

In an October 2018 analytical report, the product of a structured analytic brainstorming session, entitled “Envisioning the Emergence of Shia HVE Plotters in the US,” NCTC explained that although there have been no confirmed cases of Shi`a HVE plotting attacks in the United States, analysts identified several enabling factors that would increase the likelihood of Shi`a HVEs mobilizing to violence.71 The first is the occurrence of a “catalyzing event” such as “direct U.S. military action in Iran, sustained U.S. operations against Hezbollah in Lebanon or Syria, or the assassination of a senior Iranian or Hezbollah leader perceived to have U.S. involvement.” These events would be sufficiently significant, the analysts assessed, to “push some U.S. Shia to radicalize and consider retaliatory violence.” Such a scenario may have been theoretical conjecture at the time, but the assassinations of Soleimani and al-Muhandis surely, in this author’s assessment, meet this bar.72

For Shi`a HVE mobilization in the United States to occur, the U.S. intelligence analysts assessed, some combination of a series of other boxes would also have to be checked. Some of these boxes have been checked in the past without Shi`a HVE mobilization, but the analysts noted that “repeat occurrences of such incidents could contribute to or spark radicalization.” The analysts added that these include catalyzing events other than U.S. military action, such as Shi`a leaders and clerics calling for violence in the United States; Israeli or Sunni Arab government lethal operations targeting Iran, Hezbollah, or other Shi`a; or anti-Shi`a activity in the United States.73

The potential for Shi`a HVE mobilization to violence increases, the report continued, if the catalyzing event occurred in conjunction with “radicalization enablers.” Such enablers could include, for example, charismatic U.S.-based radicalizers, perhaps people who have fought with Hezbollah or other Shi`a militant groups overseas, promoting Shi`a grievances and advocating attacks. Alternatively, social-media influencers tied to Iran or Hezbollah or independent Shi`a websites promoting Shi`a grievances could conduct influence operations intended to sow discord among Shi`a in the United States and mobilize them to violence. The NCTC report notes, for example, the pro-Hezbollah “Electronic Resistance” social media outfit, which supports Hezbollah but is not controlled by it and which spreads Shi`a extremist material online. NCTC refers to these as “Shi`a cyber actors.”74 If Shi`a media, which is dominated by Iran and its proxies, began to open sanction retaliatory violence, that too, according to the NCTC report, would serve as an enabling factor for Shi`a HVE mobilization.

As it happens, Iran runs extensive digital influence operations, including using Instagram accounts to spam the White House and Trump family after the Soleimani assassination with images of coffins draped in U.S. flags with the caption “prepare the coffins.”75 Iran’s IRGC also disseminates its ideological training materials online in Farsi. A new study by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change details how IRGC ideological training documents “propagate the idea that there is an existential threat to Shiism and Shia Muslims from a ‘[Sunni] Arab-Zionist-Western axis.’” Among the report’s key findings is that the worldview within which the IRGC ideological training is framed is extremist and violence. “It identifies enemies—from the West to Christians and Jews, to Iranians who oppose the regime—and advocates supranational jihad in the name of exporting Iran’s Islamic Revolution.”76

And there are signs that Shi`a militia groups themselves are producing material on social media aimed at radicalizing Shi`a and mobilizing them to violence. A tweet by a Kata’ib Hezbollah spokesperson on January 3, 2020, right after the Soleimani hit, encourages volunteers to undertake “martyrdom operations against invading Crusader foreign forces” by noting that the first to register would be the first to be martyred.77 A post on Twitter dated February 5, 2020, shows a photograph of what it says is Kata’ib Hezbollah’s registration form for those interested in carrying out suicide operations targeting U.S. forces in Iraq.78

A variety of factors inhibit the emergence of Shi`a HVE activity in the United States—not a single case of Shi`a HVE activity has been reported to date—including the fact that Shiism is hierarchical, and there is therefore an inherent disincentive to carrying out truly inspired, lone-offender attacks absent direction from senior Iranian, Hezbollah, or other authority figures. But in the event that radicalization enablers follow one or more catalyzing events, NCTC argued, these would “probably increase the number of Shia HVEs or accelerate their mobilization to violence by amplifying anti-US and pro-Shia rhetoric among Shia audiences in the US.”79

In another scenario, Shi`a HVE mobilization would not necessarily have to start from zero. A case could be envisioned in which a member of the Shi`a community in the United States is self-radicalized with the help of online extremist Shi`a messaging, but still more likely is that someone already involved with a Shi`a extremist group is mobilized to action on their own, independent of the organization.

Such concerns warrant attention, especially in light of the historical precedent. In August 1989, a Hezbollah operative died while preparing an explosive device in a London hotel.80 Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh intended to assassinate Salman Rushdie, the author whose 1988 publication, The Satanic Verses, prompted Ayatollah Khomeini to issue a fatwa condemning him to death.

A Lebanese citizen born in Guinea, Mazeh joined Hezbollah as a teenager. He visited the family village in Lebanon before making his way to England via The Netherlands. Later, in the context of discussing Khomeini’s Rushdie fatwa, a Hezbollah commander told an interviewer that “one member of the Islamic Resistance, Mustafa Mazeh, had been martyred in London.”81 According to a 1992 CIA assessment, attacks on the book’s Italian, Norwegian, and Japanese translators in July 1991 suggested “that Iran has shifted from attacking organizations affiliated with the novel—publishing houses and bookstores—to individuals involved in its publication, as called for in the original fatwa.”82 A shrine dedicated to Mazeh was erected in Tehran’s Behesht Zahra cemetery with the inscription: “The first martyr to die on a mission to kill Salman Rushdie.”83

Conclusion

Speaking at a ceremony marking the 40th day since Soleimani was killed, IRGC Commander Major General Hossein Salami warned both Israel and the United States, “If you make the slightest error, we will hit both of you.”84 A day earlier, Iran’s foreign ministry released a statement—on February 12, 2020, the anniversary of Imad Mughniyeh’s death—warning that “the Islamic Republic of Iran will give a crushing response that will cause regret to any kind of aggression or stupid action from this regime [Israel] against our country’s interests in Syria and the region.”85

In fact, it is likely that any Iranian international terror campaign in response to real or perceived action against its interests—be it the assassination of Qassem Soleimani in Iraq or airstrikes in Syria targeting Shi`a militias or weapons transfers destined for Hezbollah—would include actions taken by Shi`a militants of varying nationalities operating at Iran’s behest. Under Soleimani, the Quds Force built up its Shi`a militant foreign legion, and as a consequence of their shared experience fighting in Syria and Iraq, these proxy groups are both battle-hardened and strongly committed to Iran. For many, fighting in Iran’s foreign legion is all they have known for the past several years. It only makes sense for Iran to deploy these fighters to new theaters, be they battlefronts or terror networks. Doing so provides Iran with reasonable deniability, and enlisting operatives traveling on a variety of non-Lebanese and non-Iranian passports may allow them to fly under the radar of law enforcement and intelligence services. Indeed, as noted in this piece, both Hezbollah and Iran have already started using these kinds of operatives for terrorist missions, so there is every reason to think they will continue to do so. Hezbollah has groomed Shi`a militants from a wide range of groups, and law enforcement authorities now worry Iran may be actively pursuing a strategy of radicalizing and mobilizing lone offenders to carry out attacks of their own out of solidarity with, but without explicit foreign direction from Iran or Hezbollah.

But the most likely scenarios for near-term ITN operations targeting the United States or its allies involve attacks on U.S. and other forces in the region and a wide range of cyberattacks.86 Iran and its proxies will undoubtedly look for opportunities to avenge the assassination of Qassem Soleimani. As counterterrorism officials try to forecast what new trends in Iranian and Hezbollah operational modus operandi might look like, they are increasingly focused on Iran’s Shi`a Liberation Army, its “fighters without borders,” and potentially seeking to radicalize lone actors—Shi`a HVEs—as tools Tehran could use to hide its fingerprints in any future attack on U.S. interests, in the region, or in the homeland. CTC

Dr. Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler fellow and director of The Washington Institute’s Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence. He has served as a counterterrorism official with the FBI and Treasury Department, and is the author of Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God. He has written for CTC Sentinel since 2008. Follow @Levitt_Matt

Substantive Notes

[a] In the September 2019 issue of this publication, then Acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire stated, “We assess that Iran will do everything they can not to go into a conventional conflict with the United States because they realize they cannot match the United States in its conventional capability.” Paul Cruickshank and Brian Dodwell, “A View from the CT Foxhole: Joseph Maguire, Acting Director of National Intelligence,” CTC Sentinel 12:8 (2019).

[b] On January 4, 2020, President Trump tweeted that the United States would target 52 Iranian sites if Tehran struck any American or American assets. See Donald J. Trump, “….targeted 52 Iranian sites (representing the 52 American hostages taken by Iran many years ago) …” Twitter, January 4, 2020.

[c] Heidariyun is an umbrella term used to connote Shi`a militants from Iraq employed by Iran to support its operations in Syria. The U.S. Treasury Department describes the Fatemiyun as “an IRGC-QF-led militia that preys on the millions of undocumented Afghan migrants and refugees in Iran, coercing them to fight in Syria under threat of arrest or deportation.” It describes Zeinabiyun as “Syria-based, IRGC-QF-led militia, composed of Pakistani fighters mainly recruited from among undocumented and impoverished Pakistani Shiite immigrants living in Iran.” See Iran Military Power: Ensuring Regime Survival and Securing Regional Dominance (Washington, D.C.: Defense Intelligence Agency, November 2019), p. 61, and “Treasury Designates Iran’s Foreign Fighter Militias in Syria along with a Civilian Airline Ferrying Weapons to Syria,” U.S. Treasury Department, January 24, 2019.

[d] As a point of comparison, two key things that led to the development and rise of al-Qa`ida were the experience its recruits gained in an active combat zone (i.e., Afghanistan) and the group’s ability to offer broad and specialized training at scale. The specialized training also created an opportunity for al-Qa`ida to talent spot. Today, a similar dynamic can be seen in the context of Iran’s IRGC, Hezbollah, and related Shi`a militant proxies, specifically experience in a conflict zone, large numbers, and robust training infrastructure.

[e] Founded in the 1950s, the Iraqi Dawa Party opposed the Baathist regime that came to power in 1968, and after 1979 Iranian revolution, a faction of the party formed a military wing based in Iran to target the Iraqi regime. This wing, tied to the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iran (SCIRI), subscribed to the Khomeinist ideology of waliyat-e-faqih, and formed close ties to Lebanese Hezbollah. After the fall of the Saddam regime, the Dawa Party entered the Iraqi political scene. See Joel Wing, “A History of Iraq’s Islamic Dawa Party, Interview With Lowy Inst. for Intl. Policy’s Dr. Rodger Shanahan,” Musings on Iraq, August 13, 2012, and Ali Latif, “The Da’wa Party’s Eventful Past and Tentative Future in Iraq,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 19, 2008.

[2] Ibid.

[6] “International Radical Fundamentalism: An Analytical Overview of Groups and Trends,” Terrorist Research and Analytical Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Justice, November 1994, declassified on November 20, 2008.

[7] “Answers to Questions for the Record from Assistant Attorney General Daniel J. Bryant to Senators Bob Graham and Richard Shelby,” U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, July 26, 2002, Marked SSCI # 2002-3253; appended to printed edition of “Current and Projected National Security Threats to the United States,” Hearing before the Select Committee on Intelligence of the United States Senate, 107th Congress, Second Session, February 6, 2002, p. 339.

[8] Matthew Levitt, “Why Iran Wants to Attack the United States, Foreign Policy, October 29, 2012.

[10] Matthew Levitt, “Tehran’s Unlikely Assassins,” Weekly Standard, August 20, 2012.

[18] U.S. v Ali Kourani, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, Testimony of FBI Special Agent Keri Shannon, May 8, 2019, p. 236 of trial transcript.

[20] Moughnieh.

[21] Ibid.

[23] Moughnieh.

[24] “Sayyed Nasrallah: Qassem Suleimani’s Shoe is Worth Trumps Head (Video),” Al-Manar, January 6, 2020.

[28] Matthew Levitt, “The New Iranian General to Watch,” Politico, January 23, 2020.

[29] Ibid.; Ali Soufan, “Qassem Soleimani and Iran’s Unique Regional Strategy,” CTC Sentinel 11:10 (2018).

[30] For background on Jamal Jaafar Ibrahimi, aka Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, see “Jamal Jaafar Ibrahimi a.k.a. Abu Mahdi al-Mohandes,” Counter Extremism Project.

[31] See, for example, Matthew Levitt, “Hizb Allah Resurrected: The Party of God’s Return to Tradecraft,” CTC Sentinel 6:4 (2013) and Matthew Levitt, “Hezbollah Isn’t Just in Beirut. It’s in New York, Too,” Foreign Policy, June 14, 2019.

[32] “Hizbullah: Avenging Soleimani Responsibility of Resistance Worldwide,” Naharnet, January 3, 2020.

[33] Hanin Ghaddar ed., Iran’s Foreign Legion: The Impact of Shia Militias on U.S. Foreign Policy, Policy Note 46, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, February 2018; Colin Clarke and Phillip Smyth, “The Implications of Iran’s Expanding Shi’a Foreign Fighter Network,” CTC Sentinel 10:10 (2017).

[34] “Escalating Tensions Between the United States and Iran Pose Potential Threats to the Homeland,” Joint Intelligence Bulletin, DHS, FBI, NCTC, January 8, 2020; document posted on the Iowa Association of Municipal Utilities website.

[35] Moughnieh.

[36] Iran Military Power: Ensuring Regime Survival and Securing Regional Dominance (Washington, D.C.: Defense Intelligence Agency, November 2019), p. 61.

[38] Ibid.

[39] For both quotes, see Nader Uskawi, “Examining Iran’s Global Terrorism Network,” Testimony submitted to the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence, April 17, 2018.

[40] Clarke and Smyth.

[41] Iran Military Power, p. 33.

[42] Ibid., p. 57.

[43] Ibid., p. 61.

[46] “Tehran-Backed Hezbollah Steps in to Guide Iraqi Militias in Soleimani’s Wake.”

[47] Haim Shaked and Daniel Dishon eds., Middle East Contemporary Survey, vol III: 1983-84 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1986), p. 405.

[49] James Glanz and Marc Santora, “Iraqi Lawmaker was Convicted in 1983 Bombings in Kuwait that Killed 5,” New York Times, February 7, 2007; Matthew S. Schwartz, “Who Was The Iraqi Commander Also Killed In The Baghdad Drone Strike?” NPR, January 4, 2020.

[50] “Iran Denies Kuwait Blast Role,” New York Times, December 14, 1983.

[53] Matthew Levitt, “Hezbollah’s Criminal and Terrorist Operations in Europe,” AJC, September 2, 2018.

[54] “USA v Ali Kourani, Complaint,” Southern District of New York, Department of Justice, May 31, 2017.

[55] “USA v Samer el Debek, Complaint,” Southern District of New York, Department of Justice, May 31, 2017.

[58] “International Radical Fundamentalism: An Analytical Overview of Groups and Trends.”

[59] “Germany Charges Man with Spying for Iran,” Associated Press, August 16, 2019.

[61] David Keyton, “Sweden Sentences Iraqi Man of Spying for Iran,” Associated Press, December 20, 2019.

[64] Barotte.

[65] Christopher Wray, “FBI Oversight,” Testimony before the House Judiciary Committee, February 5, 2020.

[66] Ibid.

[67] “Envisioning the Emergence of Shia HVE Plotters in the US,” NCTC Current, National Counterterrorism Center, October 16, 2018; document posted on the InfraGard Louisiana website.

[68] “Summary of Terrorism Threat to the U.S. Homeland.”

[69] “Escalating Tensions Between the United States and Iran Pose Potential Threats to the Homeland.”

[70] “Envisioning the Emergence of Shia HVE Plotters in the US.”

[71] Ibid.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid.

[77] Abu Ali al-Askari, “Bring lightness and gravity, and put your money and yourselves …,” Twitter, January 3, 2020, courtesy of Phillip Smyth.

[78] Ali al-Iraqi, “In the name of Allah the Merciful, the architecture of the Elamam State …,” Twitter, February 5, 2020, courtesy of Phillip Smyth.

[79] “Envisioning the Emergence of Shia HVE Plotters in the US.”

[81] H. E. Chehabi and Rula Jurdi Abisaab, Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006), pp. 292-293.

[82] “Iran: Enhanced Terrorist Capabilities and Expanding Target Selection,” Central Intelligence Agency, April 1, 1992.

[83] Loyd.

Skip to content

Skip to content